Bestowing the Tao – the Story of Lao-Tzu

Since writing my first blog six years ago about performing bearded roles at age 18, I’ve returned to the stage many more times as old men—hopefully wiser each time.

Back in 2010, I played Xiao He, the founding minister of the Han Dynasty. In 2011, I was the old abbot who kicked out the drunk-monk Lu Zhishen. In 2013, my daughter was snatched in the market by bandits. In 2014, I flew in from the heavens to bestow the wonder boy Ne Zha with the magical Cosmic Wheel. Just last year, my beards were white, gray, and golden as I transfigured from an old Taoist to an old Buddhist monk to the Dragon King of Sea.

I find that playing old never gets old. This year, I am three different Taoist masters, each with his own unique beard. Yet I am convinced that no other character has ever commanded as much reverence, held as much weight on stage, or walked as slowly as the ultimate old man, the forefather of all Taoists, the “Old Master” Lao-Tzu.

The Old Man and the Myth

Lao-Tzu is also spelled Lao-Tze, Lao-Tsu, and the current standardized spelling—Laozi. But why was he the ultimate old man? First, we don’t even know his age. According to one legend, he was born with white hair after staying in his mother’s womb for 81 years. Others claim he lived past 200.

Little else is known about Laozi's life, except that he lived around the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.E, worked as librarian in the Zhou Dynasty’s imperial archives, and possibly met Confucius for a philosophical discussion. Later in life he wrote the Daodejing, the foundational work of Taoism.

The Book of the Way

This book of prose contains the essence of Taoist wisdom. Also known as Tao Te Ching (道德經, pronounced dào dé jīng), the title is often translated as The Book of the Way of Virtue, and it is one of the most translated books in the world. In this magnum opus, Laozi expounds, often in poetic paradoxes, his views on the laws of the universe, nature, and man. In fact, the Chinese word for “morality”—dàodé—was derived from its title.

道可道,非常道。(dào kě dào, fēi cháng dào)

“The Tao is the Way that can be followed, but it is no ordinary Way.”

- Opening line of The Book of the Way of Virtue

The Old Man Reborn

Some 2,500 years after he lived, Laozi inspired a dance in Shen Yun’s 2017 program: Bestowing the Tao. And I was assigned the role of the great sage.

How do you prepare for, let alone do justice to, such a historical, even sacred role? I dove deep into his ancient work, decoding the original Chinese text (that’s the beauty of the language—that it is the same words used today), and exploring multiple English translations. By immersing myself in his words, I could begin to immerse myself in his character, and discovered all the “unspoken lines” that I needed for my dance role.

What are “unspoken lines?” As the great sage himself said, “One who knows does not speak. One who speaks does not know.” Unspoken lines (潛台詞 qián tái cí) are like a subtext. They are mental cues that assist the silent actor—the dancer—to communicate more clearly during narrative sections, to emote better through dance, and to expressively speak through body movement. Combining acting and dancing to tell a story is what a Shen Yun mini dance drama is all about, and its delivery is made possible by the versatility and vocabulary unique to classical Chinese dance.

Dancing with Unspoken Lines

So as the story of Laozi unfolds on stage during every performance, in addition to my visible movements, I’m also just listening to my inner voice.

At the start of the dance, I need to symbolically write 5,000 words onto blank scrolls of bamboo within the space of four eight-beats. It would be an awkward waste of music and emotions to see the scrolls as actually blank, so I like to visualize words appearing, and mime writing the lines: “Man follows the Way of Earth; Earth follows the Way of Heaven; Heaven models the Way of Tao; Tao models the Way of nature.”

I open up another bamboo scroll, hesitate and contemplate, as I imagine Laozi once did, to make the intangible tangible, and begin again: “Mystery within mystery; the door to all marvels.” No sooner have I finished the manuscript than the heavens open in jubilation, and immortals descend to the Earth in celebration. As I stand at the back of the stage and, together with the audience, absorb the graceful dance of the deities, I fancy that I am truly seeing the meaning of the words Shen Yun—“the beauty of divine beings dancing.”

After the deities return to their heavenly abodes, back in my library a shady official appears. He wants the scrolls. Badly. He tries to seduce Laozi with money and women in return for the scrolls, but to no avail. It becomes inevitable that, “He who acts with desire shall fail. He who tries to possess shall lose,” while “the Great Person dwells in the substantial and not in the superficial. Rests in the fruit and not in the flower.”*

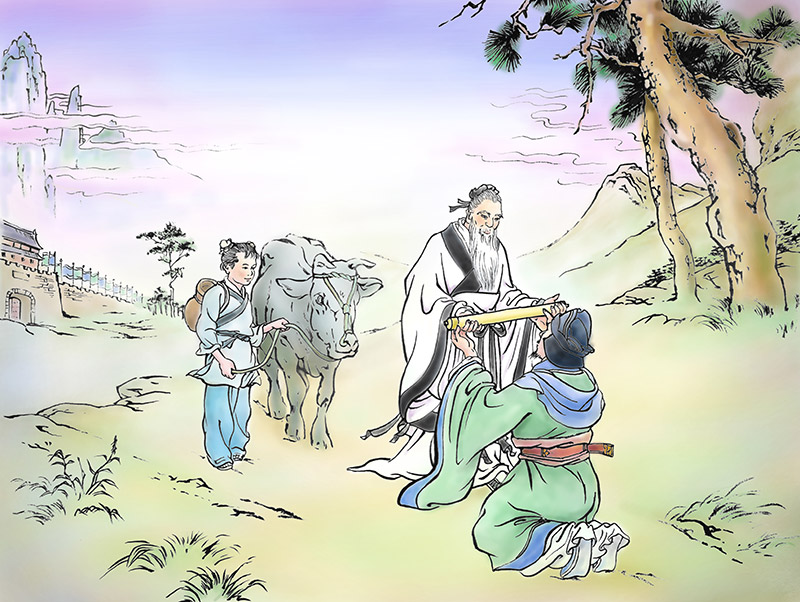

Laozi heads west, determined to leave China. The official and his henchmen give chase. Laozi, riding his ox, and his attendant continue traveling unhurried.

At the western gates of Hangu Pass, a valiant guard is waiting for Laozi. His name is Yin Xi (played by Principal Dancer Rocky Liao), and, though he doesn’t know it yet, he’s about to become a very important figure.

As Laozi draws near, the guard spots a soft purple glow heralding the arrival of the holy man. The locals welcome Laozi with a group dance and a celebration on Earth unfolds, mirroring the earlier one from the heavens.

Just then, the official and his minions appear and they aren’t messing around anymore. Swords drawn, they go straight after Laozi and the attendant boy who is carrying the sacred text. Yin Xi blocks the way to defend them and is run through by the official’s sword. Finally, Yin Xi's soldiers chase off the official and his men, who are most definitely going to have to pay.

Laozi turns around to see the brave guard Yin Xi lying unconscious on the ground, mortally wounded. I take out my Taoist gourd and pour out a few drops of elixir to heal him.

Yin Xi is revived and shocked to discover that he’s fine. Kneeling before Laozi in gratitude, he repeatedly begs the sage to teach him. “When a superior student hears of the Way, he strives to practice it diligently.”

The Master is pleased with his disciple and, knowing that he has found someone who will truly treasure his work, entrusts the precious scrolls into his outstretched hands.

And with that, Laozi’s mission is complete. He leaves his wisdom to the world and rides off into the sunset, never to be seen again.

The Way and the Force

Over time, Laozi’s influence also journeyed to the West. It even reached a galaxy far, far away. Yes—George Lucas studied Taoism before creating Star Wars.

Ever wonder why the Jedi wears white robes, trains in martial arts and meditation, uses sabers and psychic powers to defend against the dark side, and Master Yoda always speaks with such confusing grammar? There may just be a connection...

Compare the description of the Force, spoken by Obi-Wan Kenobi:

“It’s an energy field created by all living things. It surrounds us and penetrates us. It binds the galaxy together.”

To the Tao, as written by Laozi:

“There is something that is perfect in its disorder, which was born before Heaven and Earth. It stands alone and alters not. It revolves eternally without exhaustion. It is regarded as the Mother of all beings. I do not know Its name, except to call It Tao.”

The Way and the Carrier

One of my favorite quotes, though not from Laozi, sums up the idea of the Tao, ubiquitous in almost every aspect of traditional Chinese culture. It is from the I Ching, or Book of Changes: “That which is metaphysical in form is the Tao. That which is physical is only its carrier.”

Just like the human body carries the spirit, the bamboo strips carry Laozi’s words of wisdom. Dance movements carry emotions, while dance as an art form is the carrier of a beautiful experience beyond form. The stage is the carrier of our performance, a performance that aims to revive the deep culture of which Laozi was a part, a performance that carries the essence of traditional Chinese culture. Consequently, it’s through these carriers that we may hope to grasp the Way.

Being the sage that he was, maybe he knew. Maybe Laozi knew all along that two and a half millennia after riding out west, he would reappear on stages around the world to transmit his wisdom, silently letting the world know that the Way is ready to be traveled once again.

* There are dozens of translations of this book and they vary greatly from one to the other as so much of the text is open to interpretation. Most of the translated excerpts cited here are from the following sources, though in some instances I have modified the translation slightly: The Charles Muller translation of the Daodejing and Robert Eno's translation.

Ben Chen

Dancer

1. Květen 2017